One of the critiques that is levied against the Supreme Court is that is is countermajoritarian. That is, nine unelected justices can overturn legislative passed by - and signed into law by - elected representatives, or taking a more strategic view of the Supreme Court, only five justices - a simple majority of the nine that are traditionally on the Court - are sufficient to determine that a statute is invalid. This immediately raises questions about the nature of a representative democracy and whether an result that contraverts the majority is legitimate.

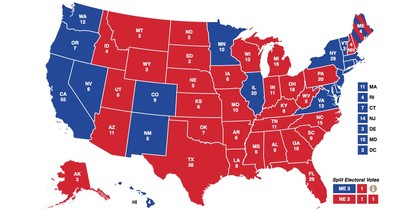

In 2000, in the Presidential election contest between Governor Bush and Vice President Gore, Bush famously won the presidency, and Gore famously won the popular vote. While the final vote has yet to be tallied in the 2016 Presidential election, it is known that Sec. Clinton lost the election, but is is increasingly likely that she will win the popular vote (While electoral behavior and shifts of demographics are important and especially so as both parties seek to define themselves and their bases going forward, they are not the focus of this post, or this blog. It is worthy to note, however, that the census will be performed in 2020, and per Article I, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution, the census shall determine representation, which, in turn, determines each state's elecoral votes), which may affect how the popular vote correlates with the electoral vote).

In the wake after the election, there has been a noticible uptick of interest in discussing the origins of the Electoral College and whether it should continue to exist in its current (or any) form. The Republicans will hold both houses of Congress and the Presidency, in addition to over thirty state houses (though not 3/4 of the Legislatures of those states), and it arguably would not be in their interest to pass legislation that would eliminate the Electoral College, as they won under the current system. More likely than reform under a Republican Congress and President, could state legislatures pass acts that reapportion how they assign their electoral votes?

Could a federal or state bill be passed and signed that served to eliminate the Electoral College? Likely not. In the event of state action, interstate compacts - agreements among and between states - need the consent of Congress, per Article I, Section 10, Clause 3. Essentially how these compacts would work is that states, who cumulatively possess 270 electoral votes, would agree that they would give their entire apportionment of votes to the candidate who wins the national popular vote, instead of the state popular vote (as currently exists in a pure form in forty-eight states and in a partial form in the other two). At present, ten states and the District of Columbia have signed on to the compact, which would trigger once the states who joined possess 270 electoral votes. However, this compact likely runs afoul of two separate provisions of the Constitution. In addition to potentially violating the Compact Clause, as described above, it also potentially is an invalid attempt to amend the Constitution from the state level, as an insufficient number of states would agree with such a compact as to trigger an amendment. Similarly to a state action, a federal action to amend the Electoral College arguably runs afoul of one of the stronger arguments that the States claim for their right to amend the Electoral College, that Article II establishes the plenary power of the states to appoint their electors in any manner as they see fit.

Where does this leave what has been termed the "National Popular Vote Interstate Compact"? Firstly, it certainly is not a product of the 2016 election. This Compact has been trying to build momentum for a number of years, and it is gaining notoriety in the past few weeks due to the election. Secondly, it is an important issue, as voters (primarily Democratic voters) see that the President of the United States, two times in the past sixteen years, has not been elected by a majority (or a plurality) of the people who voted in the election. While such an attack does not seem to undermine the legitimacy of the elected president, as the constitutional processes in place (the Electoral College) were used properly, it becomes a strategic point, as at present, the ten states and the District of Columbia who affirmed the Compact are all traditionally Democratic jurisdictions. Regardless of the partisan differences currently on display, and the seeming partisan allegiance to modifying the Electoral College (though bills to modify it have passed through Republican state legislatures), a modification to the Electoral College, in all likelihood, needs to come through as a Constitutional amendment, and not through a lesser, though potentially more expedient way.

In 2000, in the Presidential election contest between Governor Bush and Vice President Gore, Bush famously won the presidency, and Gore famously won the popular vote. While the final vote has yet to be tallied in the 2016 Presidential election, it is known that Sec. Clinton lost the election, but is is increasingly likely that she will win the popular vote (While electoral behavior and shifts of demographics are important and especially so as both parties seek to define themselves and their bases going forward, they are not the focus of this post, or this blog. It is worthy to note, however, that the census will be performed in 2020, and per Article I, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution, the census shall determine representation, which, in turn, determines each state's elecoral votes), which may affect how the popular vote correlates with the electoral vote).

In the wake after the election, there has been a noticible uptick of interest in discussing the origins of the Electoral College and whether it should continue to exist in its current (or any) form. The Republicans will hold both houses of Congress and the Presidency, in addition to over thirty state houses (though not 3/4 of the Legislatures of those states), and it arguably would not be in their interest to pass legislation that would eliminate the Electoral College, as they won under the current system. More likely than reform under a Republican Congress and President, could state legislatures pass acts that reapportion how they assign their electoral votes?

Could a federal or state bill be passed and signed that served to eliminate the Electoral College? Likely not. In the event of state action, interstate compacts - agreements among and between states - need the consent of Congress, per Article I, Section 10, Clause 3. Essentially how these compacts would work is that states, who cumulatively possess 270 electoral votes, would agree that they would give their entire apportionment of votes to the candidate who wins the national popular vote, instead of the state popular vote (as currently exists in a pure form in forty-eight states and in a partial form in the other two). At present, ten states and the District of Columbia have signed on to the compact, which would trigger once the states who joined possess 270 electoral votes. However, this compact likely runs afoul of two separate provisions of the Constitution. In addition to potentially violating the Compact Clause, as described above, it also potentially is an invalid attempt to amend the Constitution from the state level, as an insufficient number of states would agree with such a compact as to trigger an amendment. Similarly to a state action, a federal action to amend the Electoral College arguably runs afoul of one of the stronger arguments that the States claim for their right to amend the Electoral College, that Article II establishes the plenary power of the states to appoint their electors in any manner as they see fit.

Where does this leave what has been termed the "National Popular Vote Interstate Compact"? Firstly, it certainly is not a product of the 2016 election. This Compact has been trying to build momentum for a number of years, and it is gaining notoriety in the past few weeks due to the election. Secondly, it is an important issue, as voters (primarily Democratic voters) see that the President of the United States, two times in the past sixteen years, has not been elected by a majority (or a plurality) of the people who voted in the election. While such an attack does not seem to undermine the legitimacy of the elected president, as the constitutional processes in place (the Electoral College) were used properly, it becomes a strategic point, as at present, the ten states and the District of Columbia who affirmed the Compact are all traditionally Democratic jurisdictions. Regardless of the partisan differences currently on display, and the seeming partisan allegiance to modifying the Electoral College (though bills to modify it have passed through Republican state legislatures), a modification to the Electoral College, in all likelihood, needs to come through as a Constitutional amendment, and not through a lesser, though potentially more expedient way.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed