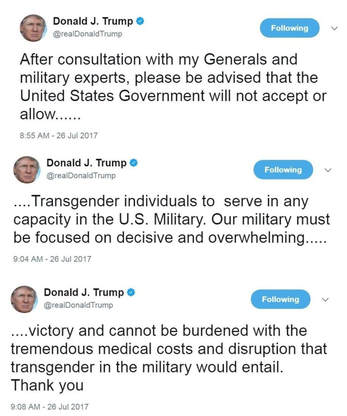

Recently, the President sent out a series of tweets (1; 2; 3) that served to state that transgender individuals could no longer serve in the United States military. Subsequent analysis and multiple outlets reported on the official process to enact such a policy (and there was a great post on Monkey Cage today that addressed several issues related to the proposed ban on transgender servicemembers), but the issue that have not been covered well have been the nature of the power itself and the reaction - and meaning of that reaction - of those senior DoD officials. Over this post and its companion next week, I'm hoping to shed light on those aspects of this conversation. Dealing with the first question first: How is it that the military can be so distinct from the American population in terms of what constitutional protections apply?

In a previous post, I examined the civil-military gap through individuals who sat down during the national anthem. Both Colin Kaepernick and a Sailor in the Navy who was in uniform refused to stand for the national anthem. While Kaepernick was not under any legal requirement to stand for the national anthem, the Navy Sailor was, and as an update, she has apparently been separated from military service.

This distinction highlights that servicemembers can be subject to laws that non-military American citizens are not subject to, and specifically, that military members can face laws that inhibit constitutional freedoms.

But, can the military make distinctions on who can enter or remain in the service? Perhaps the most well known examples of this are the ban on women in combat and Don't Ask, Don't Tell. In both cases, the military creates distinctions among servicemembers and the general population, stating that in the first instance, one gender is wholly banned from certain positions and roles, and in the second, those with one type of sexuality are eligible for entry and retention in the military, and those with another are not. At its core, all of this centers around the concept of "Good order and discipline," one of the most fundamental tenets of military service. Lawmakers and courts alike are loathe to interfere with military decision making for this reason - the military is a unique institution in what it does and how it works. It does not exist to make a profit like a private company does. It is even distinct from other state and federal service jobs in what it tries to accomplish and the expectations that it sets on its members. These fundamental differences are reflected in distinctions such as who is eligible for what job.

There are a number of Supreme Court cases that stand for this principle, and the larger doctrine is called the military deference doctrine, the notion that the Court defers to military decision making, but succinctly stated, “Judicial deference [...] is at its apogee when legislative action under the congressional authority to raise and support armies and make rules and regulations for their governance is challenged” (Rostker 1981: 70). This case centered on the question of whether it was lawful that only males were required to register for the draft. In the ten years before this, the Court began to formulate its current legal analysis and caselaw on gender discrimination, and even ruled on one gender discrimination case involving women (Frontiero v. Richardson). Reaffirming the military's decision to exclude women from combat provisions by extension, the Court held that the Military Selective Service Act was constitutional, and the gendered differences in the draft were permissible.

Certainly, the case of the President, as Commander-in-Chief, taking the steps required to enact a ban on transgender servicemembers is different than law which was approved by Congress and signed by the President. However, there are commonalities which merit examination. First, prior to former Secretary of Defense Ash Carter announcing an end to a ban on transgender military service, and not to state the obvious, there was a ban on transgender military service, which while challenged, was understood to be lawful. Beyond that, while there is a study that examines the effects of implementing a policy to permit transgender individuals to serve, a stated reason by the Commander-in-Chief based on notions of good order and discipline and unit morale will be difficult to overturn in a court of law based on the military deference doctrine.

At the heart of the military deference doctrine, and indeed why certain constitutional protections present in civilian society do not exist in the military is the simple, but challenging idea that a servicemember may be ordered to charge into an enemy position, or more practically, deploy into a combat zone, and it is expected that the order will be followed, despite the distaste, frustration, or disgust held by the person following the order. Interference by courts on equal protection or due process claims can be seen as an intrusion into the core mission and purpose of the military. Cases like Rostker and so many others affirm that position and there can be a discrepancy in what rights apply to what groups and/or individuals depending on whether they are in the military or not. At the most fundamental level, this is both the defense of the tweet that stated the policy and the most likely defense to succeed in a court of law.

One of the best examples of this can be seen in Chappell v. Wallace. In Chappell, several enlisted men aboard a ship of the United States Navy sued the ship’s Commanding Officer, four Lieutenants, and three Non-Commissioned Officers. The enlisted men claimed that they received unjust treatment based on race, and that there was a conspiracy to deprive them of statutory rights. Specifically, the men claimed that their direct supervisors, due to the race of the petitioners, discriminated against them in the issuance of duty assignments, the ranking of their performance evaluations, and the meting out of penalties. The District Court dismissed the complaint, holding that the complained-of actions were non-reviewable military decisions, that the petitioner-defendants were entitled to immunity, and that the respondent-plaintiffs had failed to exhaust their administrative remedies. The Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, dismissed the complaint, holding that enlisted military personnel could not maintain lawsuits to recover damages from their supervisors and superior officers for injuries sustained in the course of military service and as a result of alleged constitutional violations. The Court stated “The special status of the military has required, the Constitution has contemplated, Congress has created, and this Court has long recognized two systems of justice, to some extent parallel: one for civilians and one for military personnel” (Chappell 1983: 303-304).

We see that in civil rights cases involving discrimination and free speech and in equal protection cases involving eligibility to serve, the military receives distinct legal treatment because it is a distinct entity that has a special status. While there are a number of opinions on the policy change announced by the President, how it is being rolled out, whether it is wise, and whether it will ultimately be implemented, to name just a few, it is clear that the stated rationale follows a long line of judicial precedent giving wide latitude to the Commander-in-Chief and the Congress to set military policy without judicial interference that distinguishes between civilians and military members.

In a previous post, I examined the civil-military gap through individuals who sat down during the national anthem. Both Colin Kaepernick and a Sailor in the Navy who was in uniform refused to stand for the national anthem. While Kaepernick was not under any legal requirement to stand for the national anthem, the Navy Sailor was, and as an update, she has apparently been separated from military service.

This distinction highlights that servicemembers can be subject to laws that non-military American citizens are not subject to, and specifically, that military members can face laws that inhibit constitutional freedoms.

But, can the military make distinctions on who can enter or remain in the service? Perhaps the most well known examples of this are the ban on women in combat and Don't Ask, Don't Tell. In both cases, the military creates distinctions among servicemembers and the general population, stating that in the first instance, one gender is wholly banned from certain positions and roles, and in the second, those with one type of sexuality are eligible for entry and retention in the military, and those with another are not. At its core, all of this centers around the concept of "Good order and discipline," one of the most fundamental tenets of military service. Lawmakers and courts alike are loathe to interfere with military decision making for this reason - the military is a unique institution in what it does and how it works. It does not exist to make a profit like a private company does. It is even distinct from other state and federal service jobs in what it tries to accomplish and the expectations that it sets on its members. These fundamental differences are reflected in distinctions such as who is eligible for what job.

There are a number of Supreme Court cases that stand for this principle, and the larger doctrine is called the military deference doctrine, the notion that the Court defers to military decision making, but succinctly stated, “Judicial deference [...] is at its apogee when legislative action under the congressional authority to raise and support armies and make rules and regulations for their governance is challenged” (Rostker 1981: 70). This case centered on the question of whether it was lawful that only males were required to register for the draft. In the ten years before this, the Court began to formulate its current legal analysis and caselaw on gender discrimination, and even ruled on one gender discrimination case involving women (Frontiero v. Richardson). Reaffirming the military's decision to exclude women from combat provisions by extension, the Court held that the Military Selective Service Act was constitutional, and the gendered differences in the draft were permissible.

Certainly, the case of the President, as Commander-in-Chief, taking the steps required to enact a ban on transgender servicemembers is different than law which was approved by Congress and signed by the President. However, there are commonalities which merit examination. First, prior to former Secretary of Defense Ash Carter announcing an end to a ban on transgender military service, and not to state the obvious, there was a ban on transgender military service, which while challenged, was understood to be lawful. Beyond that, while there is a study that examines the effects of implementing a policy to permit transgender individuals to serve, a stated reason by the Commander-in-Chief based on notions of good order and discipline and unit morale will be difficult to overturn in a court of law based on the military deference doctrine.

At the heart of the military deference doctrine, and indeed why certain constitutional protections present in civilian society do not exist in the military is the simple, but challenging idea that a servicemember may be ordered to charge into an enemy position, or more practically, deploy into a combat zone, and it is expected that the order will be followed, despite the distaste, frustration, or disgust held by the person following the order. Interference by courts on equal protection or due process claims can be seen as an intrusion into the core mission and purpose of the military. Cases like Rostker and so many others affirm that position and there can be a discrepancy in what rights apply to what groups and/or individuals depending on whether they are in the military or not. At the most fundamental level, this is both the defense of the tweet that stated the policy and the most likely defense to succeed in a court of law.

One of the best examples of this can be seen in Chappell v. Wallace. In Chappell, several enlisted men aboard a ship of the United States Navy sued the ship’s Commanding Officer, four Lieutenants, and three Non-Commissioned Officers. The enlisted men claimed that they received unjust treatment based on race, and that there was a conspiracy to deprive them of statutory rights. Specifically, the men claimed that their direct supervisors, due to the race of the petitioners, discriminated against them in the issuance of duty assignments, the ranking of their performance evaluations, and the meting out of penalties. The District Court dismissed the complaint, holding that the complained-of actions were non-reviewable military decisions, that the petitioner-defendants were entitled to immunity, and that the respondent-plaintiffs had failed to exhaust their administrative remedies. The Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, dismissed the complaint, holding that enlisted military personnel could not maintain lawsuits to recover damages from their supervisors and superior officers for injuries sustained in the course of military service and as a result of alleged constitutional violations. The Court stated “The special status of the military has required, the Constitution has contemplated, Congress has created, and this Court has long recognized two systems of justice, to some extent parallel: one for civilians and one for military personnel” (Chappell 1983: 303-304).

We see that in civil rights cases involving discrimination and free speech and in equal protection cases involving eligibility to serve, the military receives distinct legal treatment because it is a distinct entity that has a special status. While there are a number of opinions on the policy change announced by the President, how it is being rolled out, whether it is wise, and whether it will ultimately be implemented, to name just a few, it is clear that the stated rationale follows a long line of judicial precedent giving wide latitude to the Commander-in-Chief and the Congress to set military policy without judicial interference that distinguishes between civilians and military members.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed